PIXAR

Innovators or Rip-Off Artists?

PIXAR

Innovators or Rip-Off Artists?

In a recent online post by noted film analyst / all-around ultra-geek Roger Ebert, the celebrated critic called PIXAR the only true Superstar Studio left in Hollywood. What Ebert means by that statement is that PIXAR is the last development house in mainstream media that exists (and succeeds) based simply on brand name appeal. Odds are, you don t give half a damn who is doing the voices in their films, or even what the subject matter of said film is - over the last fifteen years, we have come to equate PIXAR with high-quality, high-concept entertainment, and that is THAT.

You don t need me to tell you the influence PIXAR has had on both the world of movies and animation in general. Ever since Toy Story in 1995, the industry has shifted towards an almost all-CGI movement, and there is no denying that PIXAR is the head of the charge when it comes to delivering such entertainment. Not only has PIXAR greatly influenced animated filmmaking - it has pretty much dictated it s very future.

Before you get into a discussion of PIXAR movies, you really have to talk about PIXAR as a company first.

PIXAR originally began life as an offshoot of Industrial Light and Magic (a special effects group best known for working on a number of George Lucas productions), and was bought out by Steve Jobs in 1986 (which means that, for all intents and purposes, Apple is the number one shareholder of Disney at the current.) From there, PIXAR was INTENDED to be a hardware producer, but their line of computers that specialized in Renderman animation were about as successful as the gross profits of From Justin to Kelly. To cut losses, the company began doing a number of CGI commercials for everybody from Tropicana to Listerine. Unimpressed with the lack of revenue, Jobs sold off PIXAR s hardware division and splintered the animation studio, which was quickly approached by Disney. After a three movie deal was signed at the relatively low price of $26 million (in 1994 dollars, no less), the skeleton crew of animators began work on a project that would soon become known as Toy Story. Eleven movies and $6.3 billion dollars in revenue later, I think it is safe to assume that $26 million investment paid off and then some.

While you really cannot give any one person credit (or blame) for whatever PIXAR has achieved, the closest guy you will find to a head honcho for the company is a fellow named John Lasseter. Lasseter is a long time animator that originally made waves with his early computer animated shorts, like Luxor Jr. and Tin Toy (which won the Oscar for best animated short in 1989). He also produced a number of Disney B-projects, including The Brave Little Toaster. Although Lasseter has not had his thumb DIRECTLY over all of PIXAR s productions, he has certainly had a major say in what projects the company elects to move forward with. And on more than one occasion, he s stated that his work has been HEAVILY influenced by pre-existing works.

At this juncture, I think there is no denying that PIXAR's movies have been, by and large, pretty freaking great. However, as great as their movies are, the one thing you cannot call them are wholly original works. Not only are PIXAR's eleven wide-release films highly derivative, some of them even border on flat out plagiarism - in fact, PIXAR has been sued NUMEROUS times by several artists, all claiming that their ideas were swiped for the company s features.

Now, the point of this article ISN'T to belittle or condemn PIXAR. Rather, the point is to demonstrate that in today s entertainment world, ideas are perpetually recycled and reshuffled, and that a lot of established concepts and stories are often re-posited for the masses, even if the makers of that very entertainment are unaware of it at the time. Now, just how unaware those producers are is a matter of debate - and I do not think that any modern company has found a way to blur inspiration and derivation as much as America s sole Superstar Studio.

To demonstrate this, we'll examine all eleven mainstream, feature-length PIXAR releases to date, and compare them with pre-existing works which may or may not have inspired the company s films. A lot of this is just mere conjecture, but in a lot of other cases, the evidence is not just overwhelming, but pretty damning, to boot.

And so, the court is in session: Is PIXAR a company that has succeeded on its own ideas, or has the mega-media empire shamelessly been built upon the swiped work of others? Well, let's take a look at the accusations, film by film. . .

The Toy Story Series

The CASE FROM PIXAR:

The Toy Story franchise, if you believe the company line, stems from John Lasseter s 1989 short film The Tin Toy. If you picked up a VHS copy of Toy Story in 2000, you would ve seen this short, as it was included on the video cassette re-pressing of the film before the release of Toy Story 2.

By now, we are all well aware of the finer points of the film: a Cowboy toy feels threatened by the appearance of a new, space-themed action figure, and throughout the film, the two embark on an adventure that ultimately rectifies their hostilities against one another. That, of course, has been a hallmark of Western literature for the last 500 or so years - the old enemies becoming friends through communal understanding chestnut, ostensibly. The film is also populated by a menagerie of other characters, many of which are patterned after real-life consumer templates - I am not sure just how much Mattel paid to have Mr. Potatohead included in the film, but I am pretty sure that it paid PIXAR's light bill for at least a year or two.

A 2000 follow-up (which was originally planned as a straight-to-video release) featured Woody getting abducted and separated from his friends, and a majority of the plot centralized around his friends trying to recover him from the nefarious clutches of a possessive collector. The franchise came to an end in 2010, with a third installment which featured the toys embarking upon a journey to reunite with their master, who was now perhaps too old to enjoy their company.

Certainly, the series makes use of a number of thematic tropes, but how far does the franchise capitalize on the established works of others? Well, as it turns out. . .

The CASE AGAINST PIXAR:

OK, so the idea of a world populated by self-conscious, animated toys is nothing new. In fact, the idea of a world populated by self-conscious, animated toys that possess prejudices, jealousies, and misunderstandings that mirror our real-life concerns and hostilities is really nothing new, either.

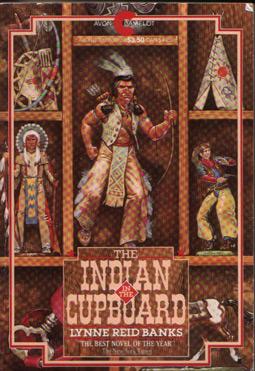

Both The Indian in the Cupboard and the Christmas Toy are works that predate Toy Story, yet contain the exact same premise for the original plot of PIXAR s breakthrough film. Hell, not only do both of these properties predate Toy Story, they even predate The Tin Toy, the Lasseter-produced short that SUPPOSEDLY inspired Toy Story to begin with!

Now, I know what you're thinking: if Toy Story went into production in 1994, and Indian in the Cupboard was released in 1995, doesn t that mean that Indian in the Cupboard is the rip off and not the other way around? Well, not so fast, because Indian in the Cupboard is actually based upon a series of books, the first which was released in 1980. The storyline for the book is practically identical to Toy Story s key narrative, and both even feature animated cowboy toys. There is something of a role reversal here, as the cowboy toy represents a sort of alien presence, whereas the Indian toy represents traditionalism and the familiar - so basically, the Indian is Woody, and the cowboy is Buzz Lightyear.

But just you wait! In 1986, a TV movie (produced by Jim Henson s Muppet Company) called The Christmas Toy hit the air. The movie was about a tiger toy that felt as if he was going to be replaced by a new toy his master received at Christmastime - which, would you believe it? - just so happens to be a SPACE themed toy (although, in this case, a female). Like Toy Story, the film featured an ensemble cast of characters modeled after generic playthings, who all helped the two combatant toys learn to set aside their differences and unite in friendship. And oh yeah, that space-themed toy? It REFUSES to believe that it is a toy, too. So yeah, not only is it LIKE Toy Story. . .it pretty much IS Toy Story.

Now, what about the sequels? While the original film was obviously patterned after two pre-existing works, just how much outside influence went into Toy Story 2 and 3? Well, a lot, as a matter of fact.

For all intents and purposes, Toy Story 2 was a remake of Follow that Bird, which for those of you not in the know, was a feature length Sesame Street movie produced in the mid 1980s. The story revolved around Big Bird leaving his familiar confines to join his (her?) brethren, only to get captured by a single-minded collector that had no intentions of letting him (her?) see his (her?) Sesame Street friends ever again. And so, Oscar, Bert, Ernie and the rest of the gang decided to band together and rescue their expatriate amigo (amiga?). . .so yeah, Toy Story 2 is NOTHING at all like that movie.

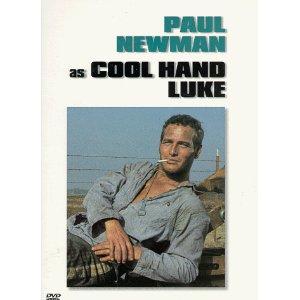

The producers of Toy Story 3 pretty much said they ripped off a number of prison movies for the plot structuring of the last installment of the franchise. I suppose the two most obvious inspirations in that regard are The Great Escape and Cool Hand Luke. . .it is BEYOND obvious that the sadistic Lotso Hugginbear was modeled after the sadistic warden in the latter film. The only thing that was missing there was a scene where he tells Buzz that he had a failure to communicate with him.

However, the most obvious - and bizarre - influence on the last installment of the Toy Story franchise is The Brave Little Toaster, which was actually produced by John Lasseter, the guy RESPONSIBLE for Toy Story in the first place. That means that Toy Story 3 exists as a rip-off of a guy s OWN work - which may or may constitute plagiarism, pending the plaintiff and defendant are wearing the same shoes.

The opening scene in Toy Story 3 is practically identical to the opening of the Brave Little Toaster - a bunch of outdated, archaic objects are secretly pining for the love of their master, who as it turns out, is soon to head off for college. Later on, the ragtag group of things find themselves in a dump, and even find themselves staring down certain death in an industrial incinerator. Perhaps Toy Story 3 represents Lasseter's career coming full circle, or maybe, he just ran out of ideas. Either way, it is glaringly apparent that the 1987 flick had a profound influence on the final chapter of the Toy Story saga, and perhaps even proved the veritable origin of the multi-billion dollar series.

A Bug's Life

The CASE FROM PIXAR:

The second mainstream release from PIXAR was this 1998 film about a cowardly ant that is instructed to assemble a civilian army to defend a sleepy hamlet from marauding grasshopper invaders. The lead character eventually assembles a makeshift defense squad, even though the troops he leads are actually circus performers that live underneath a garbage-strewn trailer. Through hard work, ingenuity and steadfastness, the ants eventually manage to hold off their mantis occupiers, and find themselves ultimately living in harmony with their ex-oppressors.

The CASE AGAINST PIXAR:

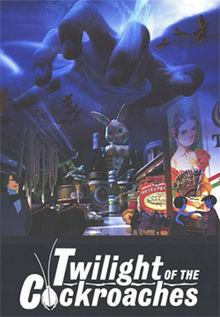

So, you re thinking about the early 90s, and you recall a certain bug-themed animated flick with realistic visuals, which was ostensibly a parable for warfare and the unsanitary nature of modern human life. You may have even saw it on the fledgling Cartoon Network a time or too, and if you re like me, it probably gave you a good case of the willies, as well.

The name Twilight of the Cockroaches may not sound familiar, but as soon as you hear the storyline, it should ring a very familiar bell. It s actually a Japanese film that blends live action with animation - essentially, it is about this guy that lives in a cockroach infested apartment, but the bachelor and the bugs live in perfect harmony. The roaches (who are anthropomorphized to the point of absolute creepiness) have basically formed a sub-society within the mess and gunk of the guy s pad - a plot point that was, ahem, borrowed, for A Bug s Life. The movie also served as the inspiration for the forgotten MTV sort-of OK movie Joe s Apartment, but that s kind of beside the point for this article. Long story short, the idea of insects living in human-like social strata, in human-like environmental conditions, is really nothing new at all in popular media.

Now, as far as the plot of the film, the guys at PIXAR owe a royalty check to two estates: one for Akira Kurosawa, and the other for Aesop. You see, A Bug s Life not only copies the plotline from Kurosawa s legendary Seven Samurai, the movie itself is essentially a remake - albeit, with grub worms instead of starving Ronin. And if you are wondering why the plotline of ants and grasshoppers feuding sounds vaguely familiar, that s because the movie is basically a derivation of Aesop s fable The Ant and The Grasshopper, which has been infused and reinterpreted in scores of media productions over the last 500 or so years, from baroque art paintings to Walt Disney anti-FDR propaganda shorts from the 1940s.

Monsters, Inc.

The CASE FROM PIXAR:

The 2001 release from PIXAR featured an underground, corporate-America like infrastructure that served as the anchor for a fairly straightforward monster yarn. You see, monsters do EXIST, but they exist for a reason, as the underground economy of Monster World is fueled by a commodity derived from the screams of children. The monsters take great pride in their work, but actually live pretty buttoned down, humdrum lives in their off hours- scaring children is simply a job, and others are certainly more efficient at it than others. Monster World is such a high uncertainty avoidance bureaucracy that when a child accidentally stumbles into their domain, they denizens of the extra-dimensional plane have no idea how to react or what to do - meaning the monsters, by and large, are more afraid of people than the other way around.

The CASE AGAINST PIXAR:

Well, the idea of monsters existing in a scare-based, underground economy is nothing new, either. In 1989, Howie Mandel and Fred Savage starred in a film called Little Monsters, which was about. . .well, the exact same damn thing Monsters, Inc. was about, fundamentally. The only difference (if you want to call it a difference at all) is that the monsters in the earlier work emerged from underneath beds, whereas in PIXAR's film, the monsters were linked to our world through a series of closet based portals. Hell, the character of Sully from Monsters Inc even seems to be an homage to Howie s character in the 1989 film, if you really take a good gander at the two side by side.

That, and the idea was recycled yet again in the 1990s Nickelodeon series AAAHH! Real Monsters, which featured a.) a machine which absorbed children s screams, b.) a monster with inferiority problems stemming from his overt cuddliness and c.) the idea of monsters attending a school in order to learn the tricks of the scaring trade. Unless you have been living under a rock for the last two years, you would know that a sequel to Monsters Inc. is currently on track for a 2013 release - which is currently titled Monsters University, and is about. . .well, the same thing AAAHH! Real Monsters was about, essentially.

Even in terms of aesthetics, Monsters Inc seemed to borrow liberally from pre-existing character designs, and from some pretty obscure sources, too. For example, who would have thunk that a one-off appearance on Pee Wee s Playhouse would have lead to a character that sold millions of key chains, plush dolls and lunchbox accessories?

Finding Nemo

The CASE FROM PIXAR:

Finding Nemo is a film about a young clown fish, with a fin defect, who has an overprotective father. On the first day of classes (why else do you think they call it a school of fish?), Nemo ends up separated from his peers, and his father must traverse a wide, endless sea in order to reclaim his son. In order to relocate his offspring, he enlists the aid of a number of kooky characters, from a fellow fish with short term memory loss to a collection of surfer-stoner turtles. At the end of the film, Nemo is reunited with his father, and the two learn a valuable lesson about the role of community and civic altruism.

The CASE AGAINST PIXAR:

You know, fate has a funny way of sneaking up on you. I saw Finding Nemo for the first time in 2004, and the very next day, I watched John Ford s The Searchers in my 12th grade cinema class. Needless to say, I noted a number of similarities between the two stories, beginning with the overall narrative of a lost child being reclaimed by a dude that really has no qualms for his personal safety anymore. Of course, this is a theme that has been used a bajillion times in countless forms of media since the advent of the printing press, so it is kind of hard to accuse PIXAR of blatantly copying a John Wayne film, when said John Wayne film was just mimicking about a number of stories that came before it. You could say that Finding Nemo is a swipe of The Searchers, but you could also say it is a swipe of Not Without My Daughter, a made for TV movie about a mother that travels to the Middle East in order to recover her missing daughter. And in that, you can even accuse the film of being a swipe of ANOTHER Disney property, The Rescuers, which was basically an adventure yarn about a group of kooky character in charge of recovering a missing child. However, you really cannot say that PIXAR blatantly copied any film for Finding Nemo. Now, European children s literature, on the other hand. . .

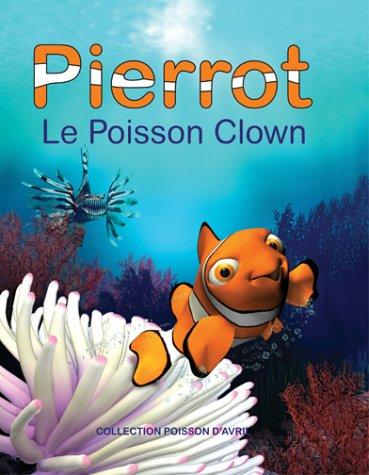

Say hello to Pierrot Le Poisson Clown, the titular character of a French children s novel written by Franck Le Calvez. . .in 1995, almost a full eight years before Finding Nemo hit theaters. The novel (and since I cannot read French, I am trusting the Babblefish interpretation here) is about a clown fish, who is separated from his father. . .so, by and large, it is the role reversal of the PIXAR release. Pending your rods and cones are not firing properly and you cannot see the crazy ass similarity between Pierrot and Nemo, I guess it would not surprise you to realize that Le Calvez ended up suing PIXAR for copyright infringement - in a case that Le Calvez eventually wound up losing.

The Incredibles

The CASE FROM PIXAR:

The 2004 release from PIXAR focused on the traditional suburban nuclear family - although, in this instance, the family in question is a group of ex-super heroes, who have all retired from crime fighting after some lawsuit-happy suicide-attempters took them to court. Meanwhile, an ex-fan boy has decided to take the route of the archetypical super villain, and even threatens to unleash the most horrendous plague ever bestowed upon the face of the earth - a consumer product that would make everyone a superhero. Yeah, I know, what a scumbag. Ultimately, the family decides to break the law and put on the skin tight spandex once more, in a last hurrah against the forces of evil - a display of bravery and courage which, presumably, turns the tide of public opinion back to their favor.

THE CASE AGAINST PIXAR:

Well, if you are going to make a movie about superheroes, even generic ones, be prepared for your work to be compared and critiqued alongside pre-existing comic book characters. And in the case of The Incredibles, two popular comic franchises IMMEDIATELY spring to mind.

The first (and absolutely ridiculously obvious) one is the Fantastic Four - which, in my day, was about a family of crime fighters that all wore matching regalia. The powers of the Incredibles seem to be a direct homage to the Fantastic Four - although, I am guessing PIXAR felt the need to replace The Human Torch with the Flash, you know, just in case Marvel got all uppity about things like blatant copyright infringement and violation of intellectual property rights. And yes, the irony that Disney ends up owning BOTH IPS five years down the road is NOT lost on me. That, AND the main villain of the film appears to be based upon legendary Marvel rogue Dr. Doom. . .although to be fair, Dr. Doom is such a Vaudeville-like character that just about EVERY outlandish bad guy in media seems to be comparable to him.

As far as where the outlawed hero subplot comes from, look no further than Alan Moore s legendary Watchmen mini-series from 1987. Of course, in those comics, the ban came about via the divine edict of Richard Nixon and NOT excessive class action lawsuits, but by and large, it s the same deal we re talking about here.

That said, perhaps the single greatest influence on The Incredibles wasn t a comic book, but rather, an entire political ethos. It is no secret that the guys at PIXAR are by and large some pretty open Republican supporters - which may or may not explain why John Ratzenberger is in EVERY single one of their productions, but I digress. Seeing as how the film came out JUST in time for the 2004 presidential election in the United States, one can say that The Incredibles is basically the conservative riposte to Fahrenheit 9/11. Consider the following: Frenchmen, bureaucrats and lawyers are seen as foes that are just as morally bankrupt as terrorists, the mother gives her children a very Donald Rumsfeld like lecture about the ruthlessness of the enemy before going into battle, and the entire movie positively drips an Objectivist vibe that makes the production seem like the brainchild of Alan Greenspan and Ron Paul. In many ways, you can say that The Incredibles was indeed a rip-off. . .from the pages of Milton Friedman and William Buckley's playbooks, that is.

The CASE FROM PIXAR:

Lightning McQueen is a young, up and coming hotshot in the racing circuit with a serious attitude problem. After taking a detour on the Interstate, he finds himself in the middle of a backwoods community, ultimately forced to do community service because he cannot keep his bumper shut during a court hearing. Although Lightning initially HATES and ridicules everyone (err, every-car) in the community - including cars voiced by Larry the Cable Guy and that dude on the salad dressing bottle - he comes to realize the quaint charm of the town, and ends up appreciating its honesty and simplicity when compared to the glitz, glamour and vapidity of the so-called big time.

THE CASE AGAINST PIXAR:

You know, sometimes, these things are so freaking obvious that NO one seems to make the association that is right under our noses. Case in point?

I mean, REALLY. How in the blue hell can anyone NOT see the connection between the film and the long-running Chevron ad campaign, which by the way, has been in operation SINCE 1995? If we were REALLY in the mood to mete out some I.P. justice, we would not a far stronger word than rip-off, that is for sure.

In the defense of PIXAR, however, you have to admit that anthropomorphic automobiles is absolutely nothing new in the world of animation. As soon as the Model T rolled off the assembly line, there were guys with pen and paper drawing giant eyeballs on them, and I assume that ALL children have noticed how the headlights and grills on vehicles sort of resemble faces, so in this instance, we will let the allegations slide.

However, the similarities between Cars and a certain Michael J. Fox vehicle (get it?), we simply cannot.

Doc Hollywood was a 1990 movie staring the ex-Marty McFly playing a New York surgeon on his way to L.A. He ends up getting a speeding ticket in a small South Carolina burgh, and after sassing off to the judge, he finds himself forced to do physician work in the town as community service. Initially, he thinks everybody in town are a bunch of rubes and hicks, but after his service is up, he begins to appreciate and like their simple ways, and finds their way of life preferable to the helter-skelter, phony nature of California life. So, the guys at PIXAR may say that the film was inspired by automobile racing and small-town America, but I think we ALL KNOW where the basic premise of the film was, ahem, borrowed.

The CASE FROM PIXAR:

Ratatouille is a film about a rat named Remy, who grows tired of his boring, impoverished life in the countryside. Fleeing near death, Remy is separated from his family and finds himself, in of all places, Paris - which he actually has a firm understanding of thanks to a lifetime of watching cooking programs on television. Remy eventually befriends a lowly mop boy, transforming him into a world renowned chef through an elaborate ruse which involves Remy controlling the youngster by yanking on tufts of his hair. Eventually, Remy is reunited with his family, which forces him to choose what is more important in his own life - personal success, or familial obligation.

THE CASE AGAINST PIXAR:

So, we have ourselves a movie about a displaced mouse, who finds himself on an adventure to reunite with his family - although in the process, he uncovers personal success and kind of forgets about the whole family subplot altogether, until they show up and force the main character to make a tough decision about individual and collective want.

OK, so it is not an EXACT duplicate of the sort of beloved (OK, sort of liked) American Tail movies, but there is certainly a little bit of Fivel to be found in the main character of Remy. In fact, a lot of the backgrounds in Ratatouille remind me a LOT of the slummy, urban environments you would see in the earlier series. Of course, the animated rodent subplot is as old as cartoons themselves, so maybe, JUST maybe, it is nothing more than coincidence here.

One of the things Ratatouille reminded me of during my first viewing was the ancient ABC cartoon Capitol Critters. If you do not remember the program, join the club - it was a show that ran for only a couple of episodes, in 1991, I want to believe. Anyhoo, the show, much like Ratatouille, was about media-savvy rats, and was centered around a hyper-intelligent mouse that relocated to the big city following a disaster. The joke, I suppose, was that the rats were actually influencing government affairs through certain mishaps and misadventures - much in the same way the mishaps and misadventures of Remy led to the creation of a number of critic-pleasing dishes.

Lastly, the plot element of a mouse creating foodstuffs to benefit human entrepreneurs isn t a fresh concept, either: in fact, that was pretty much the conclusion of the 1997 film Mouse Hunt, which featured a rat that (perhaps intentionally?) saved a dying family business by creating an impromptu delicacy out of cheese.

The CASE FROM PIXAR:

In the distant, distant future, Earth has turned into one gigantic dumping ground. The titular character is a robot in charge of cleaning up the planet, and one day, he meets (and immediately falls in love with) a more high tech robot sent by humans hovering in outer space. WALL-E, in a quest to woo the female robot (named Eve), gets sucked up into a massive floating community, where all of the inhabitants are mega-obese and wholly dependent on technology for even the most rudimentary of functions. Together, WALL-E and Eve most retrieve a potted plant, so that the ex-inhabitants of Earth can return to their home planet and begin civilization anew.

The CASE AGAINST PIXAR:

Are you looking for a thesis to pen for film school? Well, WALL-E is pretty much a treasure trove for students, since this movie comments and references just about EVERYTHING in it s brief, 90 minute runtime. Seriously, how many animated movies are out there that serve as criticisms of both Leninism AND Wal-Mart while simultaneously existing as praise of Buster Keaton and Steve Jobs?

To begin, let's get the HYPER obvious out of the way: WALL-E, whether intentional or not, is a complete and utter ripoff of Johnny 5 from Short Circuit. Granted, the movies really do not have that much in common - well, except that they are both about robots imbued with human-like emotions that want to forego their original programming in favor of acts of altruistic bravery. Even so, there is absolutely NO mistaking that WALL-E was inspired by the 1986 Ally Sheedy movie, and no amount of excuses from PIXAR can change our minds on that.

As far as the plot of the movie goes, PIXAR went to two VERY different wells in order to create the narrative for the film: Stanley Kubrick, and Mad Magazine.

Clearly, the movie references 2001: A Space Odyssey numerous times, from the design of the evil robot captain of the ship to the use of Thus Spoke Zarathustra in the film s climactic action scene. However, the plot itself (about a group of oppressed, unknowing prisoners being led to freedom by an integrity driven captain) is actually copped from an earlier Kubrick work - Spartacus, if you can believe it. Regarding the plot point about humans being insanely obese and dependent on technology, such was PRECISELY the subject of an early (albeit fairly popular) cartoon in Mad Magazine called The Blobs. In fact, the name of the movie itself may be an oblique homage to the artist of that very strip!

The CASE FROM PIXAR:

After the death of his spouse, a cantankerous old man decides to circumvent his eviction by turning his home into a flying contraption. Alongside a chubby Boy Scout, he embarks upon an adventure that involves evil explorers, talking dogs, and even a life lesson or two about human mortality.

The CASE AGAINST PIXAR:

Yeah, flying houses are nothing new in the world of animation. . .specifically, Japanese anime, which clearly inspired several plot points of the movie.

The powers-that-are at PIXAR have no qualms about stating the obvious influence of Hayao Miyazaki s work on their films. Heck, Lasseter even took production duties on a number of his most recent movies. In regards to Up, it is apparent that two of Miyazaki s films, Howl s Moving Castle and the Castle in the Sky, greatly influenced the plot structure of the PIXAR release. It is to be noted that both of Miyazaki s movies were predated by an anime program entitled The Flying House, which in addition to sporting the sailing abode motif, also included an affectionate robot character named SIR. . .which may or may not have influenced the character of Dug the dog in Up.

However, the greatest slight against Up, and perhaps the most damning evidence of plagiarism against ANY PIXAR release, is the existence of the 2005 Cloud Studio short Above Then Beyond. The animated film was created by a number of French student animators in 2005, and featured a narrative less plot about a widower (a female, in this case) that is given an eviction notice. Let s just say that her means of escape should be VERY familiar to anyone that has seen the PIXAR film.

I mean, VERY FAMILIAR:

Sure, sure, it COULD be coincidence. But judging from PIXAR's history, methinks some animators may have caught a certain French short while researching Ratatouille, no?

And so, both sides of the argument have plead their respective cases. There s a lot of evidence in favor of PIXAR, and there is a lot of evidence AGAINST them, as well. So, is the company guilty of swiping ideas, or are they simply paying respectful homage to a number of works that predated them?

I am no judge, so I shall not render a verdict for or against either party. The reality is, in this day and age, it is almost impossible to come up with something that has not at least been HINTED at previously. Go ahead, try to come up with a totally originally idea for ANYTHING, and I assure you that some German dude 80 years ago already dreamt it up. In the marketplace of ideals (or heck, even just the marketplace), you will find an array of ideas, concepts, notions and yes, products, that all have bases and origins in earlier things. If you can name me one WHOLLY original notion in the modern era, I will send you a basket of moon rocks and dinosaur eggs in the mail - the truth is, we re not doing anything original, because there are only so many ideas for us to work around with.

Creativity, I suppose, is about more than simple uniqueness. You can come up with a wholly unique idea, but without structuring or skillful tweaking of the idea, that wholly original concept is about as worthy of praise as a four year old s notebook doodles. Sure, it may not be derivative, but it certainly isn't artistically great, either.

Great art is all about expression, and just about all of our expressions as humans are reactionary. Great ideas are the results of people tweaking, refining and playing off great ideas that already exist - without building upon pre-existing frameworks, we really would not have anything worthwhile today. Imagine, if you will, if instead of tweaking the Model T and Babbage Computer, we decided to concoct different ideas in the name of originality. If it wasn't for so-called rip-offs, we would not have the internal combustion engine, cloud computing, or the cure for polio. The truth is, a lot of times, derivative works are not only OK, they are downright essential continuations for the species.

And in the case of PIXAR, they result in some pretty damn good movies, too.

The 2004 release from PIXAR focused on the traditional suburban nuclear family - although, in this instance, the family in question is a group of ex-super heroes, who have all retired from crime fighting after some lawsuit-happy suicide-attempters took them to court. Meanwhile, an ex-fan boy has decided to take the route of the archetypical super villain, and even threatens to unleash the most horrendous plague ever bestowed upon the face of the earth - a consumer product that would make everyone a superhero. Yeah, I know, what a scumbag. Ultimately, the family decides to break the law and put on the skin tight spandex once more, in a last hurrah against the forces of evil - a display of bravery and courage which, presumably, turns the tide of public opinion back to their favor.

THE CASE AGAINST PIXAR:

Well, if you are going to make a movie about superheroes, even generic ones, be prepared for your work to be compared and critiqued alongside pre-existing comic book characters. And in the case of The Incredibles, two popular comic franchises IMMEDIATELY spring to mind.

The first (and absolutely ridiculously obvious) one is the Fantastic Four - which, in my day, was about a family of crime fighters that all wore matching regalia. The powers of the Incredibles seem to be a direct homage to the Fantastic Four - although, I am guessing PIXAR felt the need to replace The Human Torch with the Flash, you know, just in case Marvel got all uppity about things like blatant copyright infringement and violation of intellectual property rights. And yes, the irony that Disney ends up owning BOTH IPS five years down the road is NOT lost on me. That, AND the main villain of the film appears to be based upon legendary Marvel rogue Dr. Doom. . .although to be fair, Dr. Doom is such a Vaudeville-like character that just about EVERY outlandish bad guy in media seems to be comparable to him.

As far as where the outlawed hero subplot comes from, look no further than Alan Moore s legendary Watchmen mini-series from 1987. Of course, in those comics, the ban came about via the divine edict of Richard Nixon and NOT excessive class action lawsuits, but by and large, it s the same deal we re talking about here.

That said, perhaps the single greatest influence on The Incredibles wasn t a comic book, but rather, an entire political ethos. It is no secret that the guys at PIXAR are by and large some pretty open Republican supporters - which may or may not explain why John Ratzenberger is in EVERY single one of their productions, but I digress. Seeing as how the film came out JUST in time for the 2004 presidential election in the United States, one can say that The Incredibles is basically the conservative riposte to Fahrenheit 9/11. Consider the following: Frenchmen, bureaucrats and lawyers are seen as foes that are just as morally bankrupt as terrorists, the mother gives her children a very Donald Rumsfeld like lecture about the ruthlessness of the enemy before going into battle, and the entire movie positively drips an Objectivist vibe that makes the production seem like the brainchild of Alan Greenspan and Ron Paul. In many ways, you can say that The Incredibles was indeed a rip-off. . .from the pages of Milton Friedman and William Buckley's playbooks, that is.

Cars

The CASE FROM PIXAR:

Lightning McQueen is a young, up and coming hotshot in the racing circuit with a serious attitude problem. After taking a detour on the Interstate, he finds himself in the middle of a backwoods community, ultimately forced to do community service because he cannot keep his bumper shut during a court hearing. Although Lightning initially HATES and ridicules everyone (err, every-car) in the community - including cars voiced by Larry the Cable Guy and that dude on the salad dressing bottle - he comes to realize the quaint charm of the town, and ends up appreciating its honesty and simplicity when compared to the glitz, glamour and vapidity of the so-called big time.

THE CASE AGAINST PIXAR:

You know, sometimes, these things are so freaking obvious that NO one seems to make the association that is right under our noses. Case in point?

I mean, REALLY. How in the blue hell can anyone NOT see the connection between the film and the long-running Chevron ad campaign, which by the way, has been in operation SINCE 1995? If we were REALLY in the mood to mete out some I.P. justice, we would not a far stronger word than rip-off, that is for sure.

In the defense of PIXAR, however, you have to admit that anthropomorphic automobiles is absolutely nothing new in the world of animation. As soon as the Model T rolled off the assembly line, there were guys with pen and paper drawing giant eyeballs on them, and I assume that ALL children have noticed how the headlights and grills on vehicles sort of resemble faces, so in this instance, we will let the allegations slide.

However, the similarities between Cars and a certain Michael J. Fox vehicle (get it?), we simply cannot.

Doc Hollywood was a 1990 movie staring the ex-Marty McFly playing a New York surgeon on his way to L.A. He ends up getting a speeding ticket in a small South Carolina burgh, and after sassing off to the judge, he finds himself forced to do physician work in the town as community service. Initially, he thinks everybody in town are a bunch of rubes and hicks, but after his service is up, he begins to appreciate and like their simple ways, and finds their way of life preferable to the helter-skelter, phony nature of California life. So, the guys at PIXAR may say that the film was inspired by automobile racing and small-town America, but I think we ALL KNOW where the basic premise of the film was, ahem, borrowed.

Ratatouille

The CASE FROM PIXAR:

Ratatouille is a film about a rat named Remy, who grows tired of his boring, impoverished life in the countryside. Fleeing near death, Remy is separated from his family and finds himself, in of all places, Paris - which he actually has a firm understanding of thanks to a lifetime of watching cooking programs on television. Remy eventually befriends a lowly mop boy, transforming him into a world renowned chef through an elaborate ruse which involves Remy controlling the youngster by yanking on tufts of his hair. Eventually, Remy is reunited with his family, which forces him to choose what is more important in his own life - personal success, or familial obligation.

THE CASE AGAINST PIXAR:

So, we have ourselves a movie about a displaced mouse, who finds himself on an adventure to reunite with his family - although in the process, he uncovers personal success and kind of forgets about the whole family subplot altogether, until they show up and force the main character to make a tough decision about individual and collective want.

OK, so it is not an EXACT duplicate of the sort of beloved (OK, sort of liked) American Tail movies, but there is certainly a little bit of Fivel to be found in the main character of Remy. In fact, a lot of the backgrounds in Ratatouille remind me a LOT of the slummy, urban environments you would see in the earlier series. Of course, the animated rodent subplot is as old as cartoons themselves, so maybe, JUST maybe, it is nothing more than coincidence here.

One of the things Ratatouille reminded me of during my first viewing was the ancient ABC cartoon Capitol Critters. If you do not remember the program, join the club - it was a show that ran for only a couple of episodes, in 1991, I want to believe. Anyhoo, the show, much like Ratatouille, was about media-savvy rats, and was centered around a hyper-intelligent mouse that relocated to the big city following a disaster. The joke, I suppose, was that the rats were actually influencing government affairs through certain mishaps and misadventures - much in the same way the mishaps and misadventures of Remy led to the creation of a number of critic-pleasing dishes.

Lastly, the plot element of a mouse creating foodstuffs to benefit human entrepreneurs isn t a fresh concept, either: in fact, that was pretty much the conclusion of the 1997 film Mouse Hunt, which featured a rat that (perhaps intentionally?) saved a dying family business by creating an impromptu delicacy out of cheese.

WALL-E

The CASE FROM PIXAR:

In the distant, distant future, Earth has turned into one gigantic dumping ground. The titular character is a robot in charge of cleaning up the planet, and one day, he meets (and immediately falls in love with) a more high tech robot sent by humans hovering in outer space. WALL-E, in a quest to woo the female robot (named Eve), gets sucked up into a massive floating community, where all of the inhabitants are mega-obese and wholly dependent on technology for even the most rudimentary of functions. Together, WALL-E and Eve most retrieve a potted plant, so that the ex-inhabitants of Earth can return to their home planet and begin civilization anew.

The CASE AGAINST PIXAR:

Are you looking for a thesis to pen for film school? Well, WALL-E is pretty much a treasure trove for students, since this movie comments and references just about EVERYTHING in it s brief, 90 minute runtime. Seriously, how many animated movies are out there that serve as criticisms of both Leninism AND Wal-Mart while simultaneously existing as praise of Buster Keaton and Steve Jobs?

To begin, let's get the HYPER obvious out of the way: WALL-E, whether intentional or not, is a complete and utter ripoff of Johnny 5 from Short Circuit. Granted, the movies really do not have that much in common - well, except that they are both about robots imbued with human-like emotions that want to forego their original programming in favor of acts of altruistic bravery. Even so, there is absolutely NO mistaking that WALL-E was inspired by the 1986 Ally Sheedy movie, and no amount of excuses from PIXAR can change our minds on that.

As far as the plot of the movie goes, PIXAR went to two VERY different wells in order to create the narrative for the film: Stanley Kubrick, and Mad Magazine.

Clearly, the movie references 2001: A Space Odyssey numerous times, from the design of the evil robot captain of the ship to the use of Thus Spoke Zarathustra in the film s climactic action scene. However, the plot itself (about a group of oppressed, unknowing prisoners being led to freedom by an integrity driven captain) is actually copped from an earlier Kubrick work - Spartacus, if you can believe it. Regarding the plot point about humans being insanely obese and dependent on technology, such was PRECISELY the subject of an early (albeit fairly popular) cartoon in Mad Magazine called The Blobs. In fact, the name of the movie itself may be an oblique homage to the artist of that very strip!

Up

The CASE FROM PIXAR:

After the death of his spouse, a cantankerous old man decides to circumvent his eviction by turning his home into a flying contraption. Alongside a chubby Boy Scout, he embarks upon an adventure that involves evil explorers, talking dogs, and even a life lesson or two about human mortality.

The CASE AGAINST PIXAR:

Yeah, flying houses are nothing new in the world of animation. . .specifically, Japanese anime, which clearly inspired several plot points of the movie.

The powers-that-are at PIXAR have no qualms about stating the obvious influence of Hayao Miyazaki s work on their films. Heck, Lasseter even took production duties on a number of his most recent movies. In regards to Up, it is apparent that two of Miyazaki s films, Howl s Moving Castle and the Castle in the Sky, greatly influenced the plot structure of the PIXAR release. It is to be noted that both of Miyazaki s movies were predated by an anime program entitled The Flying House, which in addition to sporting the sailing abode motif, also included an affectionate robot character named SIR. . .which may or may not have influenced the character of Dug the dog in Up.

However, the greatest slight against Up, and perhaps the most damning evidence of plagiarism against ANY PIXAR release, is the existence of the 2005 Cloud Studio short Above Then Beyond. The animated film was created by a number of French student animators in 2005, and featured a narrative less plot about a widower (a female, in this case) that is given an eviction notice. Let s just say that her means of escape should be VERY familiar to anyone that has seen the PIXAR film.

I mean, VERY FAMILIAR:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=gLHwbukUU3c

Sure, sure, it COULD be coincidence. But judging from PIXAR's history, methinks some animators may have caught a certain French short while researching Ratatouille, no?

And so, both sides of the argument have plead their respective cases. There s a lot of evidence in favor of PIXAR, and there is a lot of evidence AGAINST them, as well. So, is the company guilty of swiping ideas, or are they simply paying respectful homage to a number of works that predated them?

I am no judge, so I shall not render a verdict for or against either party. The reality is, in this day and age, it is almost impossible to come up with something that has not at least been HINTED at previously. Go ahead, try to come up with a totally originally idea for ANYTHING, and I assure you that some German dude 80 years ago already dreamt it up. In the marketplace of ideals (or heck, even just the marketplace), you will find an array of ideas, concepts, notions and yes, products, that all have bases and origins in earlier things. If you can name me one WHOLLY original notion in the modern era, I will send you a basket of moon rocks and dinosaur eggs in the mail - the truth is, we re not doing anything original, because there are only so many ideas for us to work around with.

Creativity, I suppose, is about more than simple uniqueness. You can come up with a wholly unique idea, but without structuring or skillful tweaking of the idea, that wholly original concept is about as worthy of praise as a four year old s notebook doodles. Sure, it may not be derivative, but it certainly isn't artistically great, either.

Great art is all about expression, and just about all of our expressions as humans are reactionary. Great ideas are the results of people tweaking, refining and playing off great ideas that already exist - without building upon pre-existing frameworks, we really would not have anything worthwhile today. Imagine, if you will, if instead of tweaking the Model T and Babbage Computer, we decided to concoct different ideas in the name of originality. If it wasn't for so-called rip-offs, we would not have the internal combustion engine, cloud computing, or the cure for polio. The truth is, a lot of times, derivative works are not only OK, they are downright essential continuations for the species.

And in the case of PIXAR, they result in some pretty damn good movies, too.

James Swift is a freelance writer and author of two books, How I Survived Three Years at a Two-Year Community College: A Junior Memoir of Epic Proportions and Mascara Contra Mascara: A Tale of Two Masks. Follow him on Twitter at JSwiftMedia, or subscribe to his YouTube channel at youtube.com/user/JSwiftMedia

14

Login To Vote!

More Articles From JSwiftX

Comments

22